Recent years have seen a growing interest and increasing uptake of experimental methods in government. Around the world, we see a growing number of governments taking up experimental approaches to tackle complex issues and generate better public outcomes.

We've already been exploring, researching and supporting how to enable effective experimental innovation policy and build better public services through experimental government for some time. There's the Alliance for Useful Evidence who have been critical in supporting a more systematic approach to experimentation and evidence in the UK - including the launch of multiple What Works Centres. And more recently, the Innovation Growth Lab, enabling cross-national collaboration on experimental innovation and growth policy.

But with the notable exception of Finland, where experimentation has been elevated to official government policy, there still seems to be many challenges for governments to connect the wide range of experimental approaches available with strategic policy development and implementation. We offer up some ideas.

Experimentation as a way of exploring “the room of the non-obvious”

Governments need to increase their pace in learning about which ideas have the highest potential value-creation and make people’s lives the rationale of governing.

Experimental approaches learn fast by testing assumptions and identifying what we don't know. What is there to be known about the problem and the function, fit and probability of a suggested solution? Experimentation helps fill these gaps without spending too much time or resource finding out. It helps governments dismiss bad ideas and explore others that might actually work.

Government policy labs and public sector innovation teams already do this. Units like Lab para la Ciudad in Mexico City, Alberta Co-Lab in Canada, Behavioural insights and Design Unit in Singapore, MindLab in Denmark and Policy Lab in the UK are specifically set up to promote, develop and embed experimental approaches and accelerate user-centred learning in different levels of government.

In addition, creating a culture of experimentation extends the policy options available by creating a political environment to test non-linear approaches to wicked problems. In our training, we often distinguish between “the room of the obvious” and the “room of the non-obvious”. By designing portfolios of experiments that include - by deliberate design - the testing of at least some non-linear, non-obvious solutions, government officials can move beyond the automatic mode of many policy interventions and explore the “room of the non-obvious” in a safe-to-fail context (think barbers to prevent suicides or dental insurance to prevent deforestation).

Experimentation as a way of turning uncertainty into risk

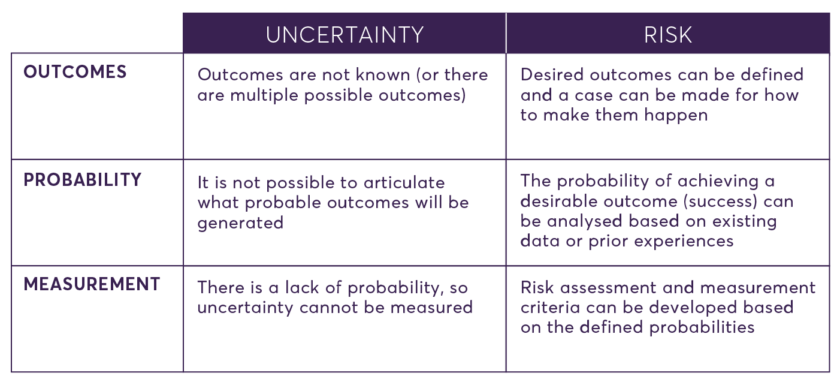

In everyday language, uncertainty and risk are two notions that are often used interchangeably; yet they are very different concepts.

Take the implementation of a solution. Risk is articulated in terms of the probability that the solution will generate a certain outcome. It is measurable (based on existing data there is X per cent chance of success, or X per cent chance of failure) and qualitative risk factors can be developed and described.

Uncertainty, on the other hand, is a situation where there is a lack of probabilities. There is no prior data on how the solution might perform; future outcomes are not known, and can therefore not be measured. The chance of success can be 0 per cent, 100 per cent, or anything in between. We just don't know.

There is often talk of the need for government to become more of a ‘risk taker’, or to become better at ‘managing risk’. But as Marco Steinberg, founder of strategic design practice Snowcone & Haystack, recently reminded us, risk-management - where probabilities are known - is actually something that governments do quite well. Issues arise when governments’ legacies can’t shape current solutions: when governments have to deal with the uncertainty of complex challenges by adapting or creating entirely new service systems to fit the needs of our time.

For example, when transforming a health system to fit the needs of our time, little can be known about the probabilities in terms of what might work when establishing a new practice. Or when transforming a social care system to accommodate the lives of vulnerable families, entirely new concepts for solutions need to be explored. “If you don’t have a map showing the way, you have to write one yourself,” as Sam Rye puts it in his inspirational example on the use of experimental cards at The Labs Wananga.

There are plenty of examples of policies that have been developed on untested assumptions and then implemented (and failed) with a “big bang”. Running experiments at an early stage is really a systematic way of turning uncertainty into a set of probabilities that, in turn, can be experimented with and managed within a more defined scope. In this sense, policy initiatives can be used as learning opportunities to deal with uncertainty in ways that create a set of useful probabilities to close the gap between uncertainty and risk.

Reflection 3: Experimentation as a way to reframe failure and KPIs

Experimental government changes how to think about failure. Usually, admitting failure means becoming a scapegoat and the centre of the blame game. But in order to accelerate learning and deal with uncertainty, there is a need to allow for learning from failure when exploring possible new ways of addressing complex challenges.

We should, according to Harvard Business School’s Amy Edmondson, draw a distinction between bad and good failures. Bad failures can be considered as preventable failures in predictable operations. Good failures, on the other hand, are often unavoidable failures in complex systems or when entering uncharted territory and dealing with high levels of uncertainty.

One of the ways that we have attempted to work with this premise is, as Michael Schrage suggests, to reframe (good) ideas as testable hypotheses. The problem with ideas is that even the good ones often fail when they are confronted with reality. In practice, ideas are never fully formed, but need to work in and adapt to a dynamic system.

"Innovation amateurs talk good ideas; innovation experts talk testable hypotheses."

The objective is to increase your knowledge about what you know to be true about the potential real-life effects of your hypothesis. Reframing ideas as hypotheses highlights the need for ongoing testing, refining and further development. It also introduces a more humble approach to change-making, allowing for an idea to be tested to understand if it actually addresses the causes of the problem at hand, and then adapted in terms of its function and fit with users (as suggested by Christian Bason in Danish Design Council’s policy experimentation approach).

Experimentation is a way to deliberately and systematically produce good failures and learn from them to avoid policies getting stuck on the wrong track. This means reframing KPIs from an almost exclusive focus on upward accountability to a more deliberate embracing of downstream learning in order to accelerate the learning of those closer to the frontline. The irony is perhaps that often governments fail because they do not know how to fail in ‘good enough’ ways.

Fortunately, there are many encouraging initiatives emerging. Among many, but perhaps most prominently, the aforementioned Finland’s Design for Government programme is strategically introducing experimentation into policy-making and public innovation initiatives. Crucially, this programme involves also developing an ethical code for conducting experiments in government. A core challenge is that most experimental programmes are inherently in the business of exploring and establishing new institutional models that deal with the authorising environment and political economy of experimentation in new ways.

Reflection 4: Experimentation on a continuum between exploration and validation

One of our main concerns when it comes to experimentation is that too often people equate experimentation in government with doing RCTs. While RCTs are certainly an important part of qualifying and validating a hypothesis and turning it into an implementable initiative, they are less useful if the understanding of the problem is unclear and the opportunity space needs to be re-imagined.

In this light, we are currently developing and testing a new framework introducing a “Continuum of experimentation”, which builds on and synthesises leading experimental initiatives in the field (see figure below). The continuum attempts to combine the methods and approaches inspired by both analytical and imaginative mindsets involved in experimentation - arguing that is not an ‘either or’ situation. Rather, there is a need to apply experimental approaches from different disciplines such as social and natural sciences, arts, data analytics and design. This is particularly in order to enable and systematically apply different experimental approaches in accordance with what you know about the problem at hand and its possible solutions (therefore there is not a strict division between categories in the continuum, but are rather dynamic, fluid and overlapping).

The continuum identifies three key categories of experimentation:

- Generating hypotheses. Shaping direction by generating multiple hypotheses for change.

- Establishing a hypothesis. Developing and establishing particular hypotheses to test their potential value-creation.

- Validating a hypothesis. Validating the fit and function of a particular hypothesis to be turned into interventions.

At one end of the continuum, where probabilities and solutions are unknown, an imaginative mindset is required. Experiments at this end of the continuum are exploratory and aim to identify new frames to generate new thinking and action (one could also use systematic solution mapping, under the assumption that the pace of experimentation on the outside is greater than on the inside). Hypothesis generation is driven by exploring options and asking ‘what if?’. In this end of the continuum, a successful output leads to the discovery of “hunches” that help generate new hypotheses to test. Speculative design is one example of the methods that employ this process of discovery.

At the other end, where probabilities are known, activities focus on justifying decisions and managing risks. This space is driven by the analytical mindset and employs rigorous scientific procedures to validate possible solutions before scaling them. It is driven by testing an established hypothesis: “if we do this, then we believe this will happen”. An experiment is successful when such a hypothesis is tested in terms of its validity and effectiveness in dealing with the problem at hand. Randomised Control Trials (RCTs) are a prominent method that are often used in this space.

In between exploring options and validating a hypothesis, there is a category of experiments that build on both the imaginative and analytical mindset. We have called this a ‘trial-and-error’ approach. This is to highlight that in this part of the experimental process, successful outputs are identifying, testing and/or challenging existing assumptions and learning about the fit and function of the potential solution: what might work (well enough) and what doesn't. A hypothesis is tested in order to understand the probabilities underpinning a potential solution as well as the unanticipated effects - good or bad - that it might have. Prototyping is a typical method that follows this trial-and-error approach to test ideas at an early stage and learn fast from failure.

As a whole, the continuum is meant to highlight that successful experimentation needs a dynamic and iterative process of shaping direction, creating a basis for redesign and legitimising decision-making. And not least that there are different questions to ask, activities to be mindful of, and methods to use throughout the experimental process.

Reflection 5: Experimentation as cultural change

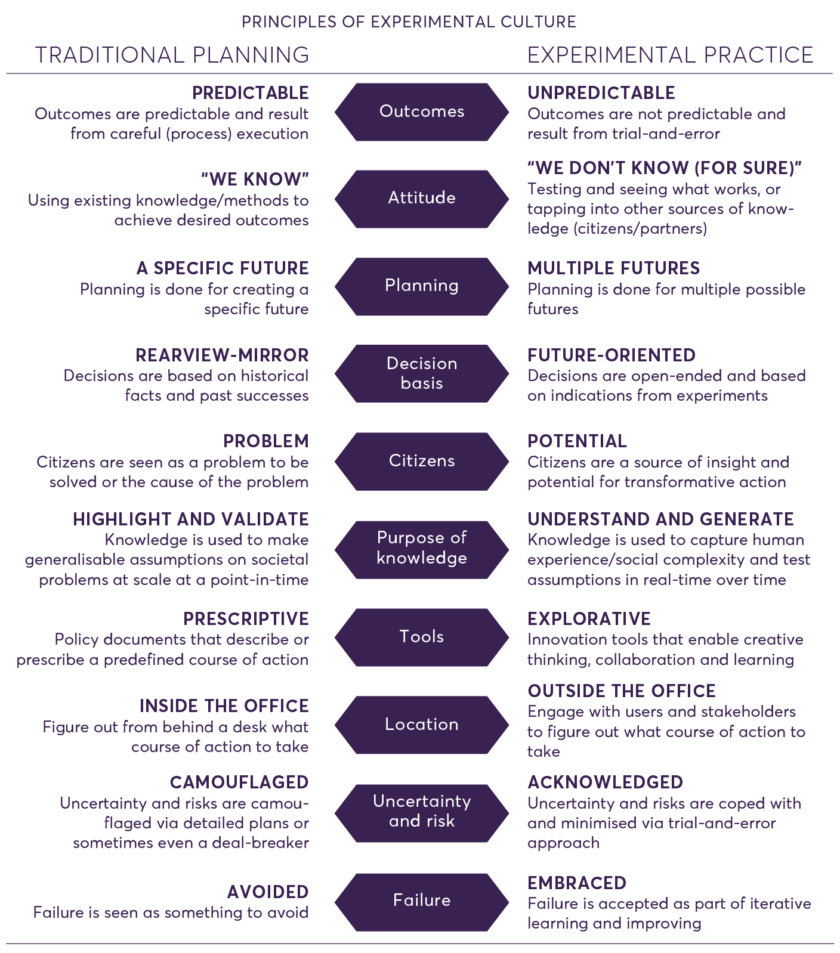

Successful experimentation relies on much more than learning a technical method, but actually implies a shift in the culture of decision-making on both strategic and operational levels of government. In one of our recent conversations a civil servant explained her biggest dilemma: “I can’t tell my minister that I don’t know. It is simply not acceptable to not have an answer ready. You have to come with a clear strategy promising a solution.”

If experimental approaches are to become effective and impactful, there is a need to influence the professional culture of public organisations. It needs to be okay and safe to say: “I don’t know, but I will do my best to find out what the (best) solution might be”. Learning to use experimental approaches, in this sense, requires much more than learning about technical methods, and needs to be applied much more fundamentally in the general perception and experience of doing problem-solving activities (similar to what Zavae Zaheer is suggesting in relation to experimental platforms).

In the Nesta Skills team, we are currently developing learning offers and capacity-building support focused on developing a new culture over time (see also Public Innovation Learning: What’s Next?). Focusing on ‘culture’ entails zooming in on what actually enables and creates useful behaviour change and encourages new ways of articulating professional judgment. This, at least, requires a change in:

- Mindset – the fundamental set of assumptions and perspectives that frame the understanding of one’s own role, practice and potential.

- Attitude – the emotional state that creates a propensity to perceive and solve problems in a particular way.

- Habits – the fundamental actions and activities that one views as essential and valuable in exercising one’s professional role.

- Functions – the core operational tasks of government (i.e. how to approach policy development, procurement, etc.) that often go unquestioned.

- Environment – the factors and elements that shape how decisions are made and how development processes are enabled and authorised.

These elements are obviously not something that shift overnight, but take ongoing in-practice learning and unlearning over longer periods of time. As usual when it comes to government innovation, a bias towards action is essential to foster cultural change. To help guide such efforts, we are developing some (re)design principles that may provide useful support in the process of making mindsets, attitudes, habits, functions and environments more accommodating to experimentation (see table below).

There are encouraging examples around the world of recognising culture as a critical aspect to enable and drive more experimentation. In the UK, the Government Digital Service is developing a new culture of citizen engagement and service design. In Canada, on a federal level the government is issuing new requirements to allocate proportion of budgets for experimentation. And on a local level, with support from InWithForward, service organisations are trialling new ways of creating space for experimentation, research and development in public service delivery. In Chile, the Laboratorio de Gobierno is running the Experimenta programme - a cross-government training movement centred around experimental approaches. And the Mohammed Bin Rashid Centre for Government Innovation in UAE is currently exploring - in collaboration with Nesta - how to foster a culture of experimentation in government.

What next?

Since these reflections are unfinished and work-in-progress, we are curious to know how they resonate with practitioners in the field of experimental government. What is important when strategically planning and doing experiments in government contexts? And which experiences should we base our R&D efforts on in order to support the growing community of practice?

Within the States of Change initiative, we will work with and support a number of governments and innovation labs on building better innovation capacity (and a culture of experimentation) in the coming months. This work will involve related topics such as HR management for innovation, ecosystems for innovation (organisational readiness) and impact assessment for building innovation capacity in government. We are very keen to hear from people and organisations that wish to be involved in this.

Collectively and in collaboration, we hope to take some steps in the right direction in order to better deal with the many challenges for governments to embed experimental approaches in their strategic policy and innovation work.