When Tomas Dominguez Vidal and his team at LABgobar stepped into the halls of Senasa, one of Argentina’s oldest institutions, they had a string of successful projects behind them. But lingering was the nagging feeling that despite their successes they hadn’t made any lasting impression on the organisations they had worked with. The transformative change they hoped for hadn’t materialised.

As a team based in central government with the mission: ‘to make a paper powered government a modern, digital one’, that was a problem. These are some of the lessons of how a team of five people got an organisation of 5000 to rethink its very role.

1. Make sure your team is diverse.

The LABgobar team are a pick ’n’ mix of skills and backgrounds. A service designer; a master in Finance now focused in neuroscience and behavioural economics, a business economist that became a strategic designer, an anthropologist, and a political scientist. The majority of them are relatively new in government, but some of them have a long — and very valuable — experience in the public sector. They’re an inclusive, creative, interdisciplinary team and that should be the norm if you care about high performing teams.

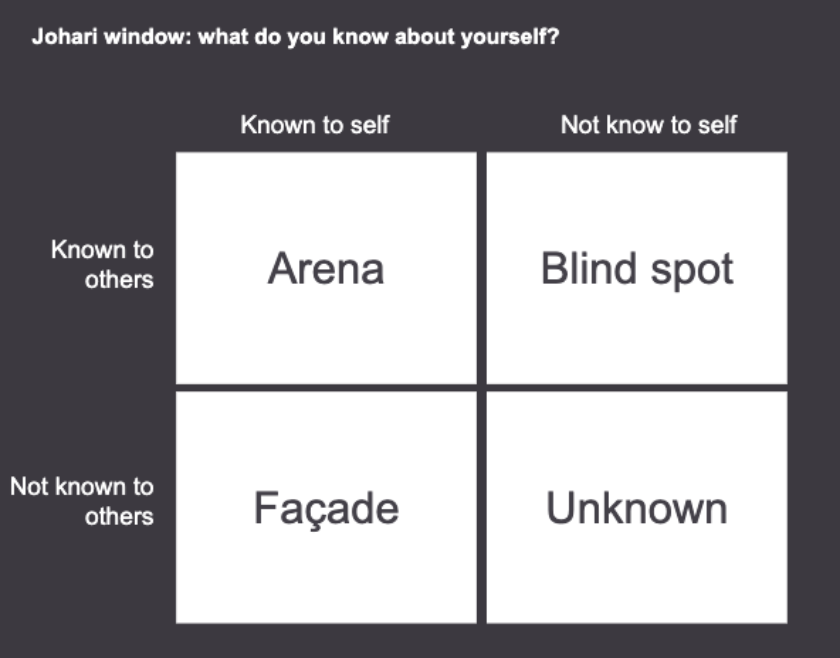

There’s value in having a different perspective and you won’t have that if you all think the same way. If you look around you and A) the faces all look the same as yours and B) you’re all good at the same thing, then take a look at Nesta’s guide to the competency framework. Those skills gaps and blindspots could be holding you back! And for a way fast way to approach then at least check your ‘unknown unknowns’ with a Johari window exercise.

2. Be method agnostic and prepared to ask difficult questions

Rather than use one specific method or approach to every problem LABgobar looked for the right approach to fit the challenge; whether those approaches were behavioural insights, design thinking, or data science and prototyping (and the rest). A diverse and inclusive team will help make sure you do what is right, rather than what you are comfortable with. You’ll be challenging each others’ biases.

It’s more important to ask good questions than present ‘oven ready’ answers even when the pressure is on to “deliver yesterday!” To ask good questions you need a level of psychological safety because good questions aren’t often the easy questions. Before piling in with the nine whys remember that the innocent method of ‘ask why’ and ‘why doesn’t this work’ can often be perceived as an attack on someone’s role and their decisions. Be kind.

3. You can make a little of your own luck. But you still need luck.

As an ‘internal consultancy’ LABgobar paid their own way with projects across government. But it wasn’t until they got a call from the President of Senasa that they really got a chance at change in a large institution. That was stroke of luck.

It wasn’t a call from the blue. They’d built up a track record on projects as wide-ranging as speeding up the time to get an industrial permit (from years to months); making more people aware of and using legal advice centers; streamlining a process that made it easier for people to pay their taxes regularly; and developing a more effective policy around youth employment. It helps when you show the thing rather than waffle on about the thing — that way people can clearly understand what you’ve been doing. Fluffy ambiguity can be immensely off-putting.

4. Earn yourself some champions. You’ll need allies.

After the call from the President, Tomas and his team started with the basics and they started right at the top, with the entire Senasa leadership team, all 24 of them. They had a shot at introducing the ‘new normal’ of modern policy work, those various methods mentioned earlier. The president of Senasa looked on.

After the first workshop, with a satisfied-but-want-more attitude, the President took the Lab’s team aside and told them to be bolder, more challenging. He wanted them pushing his leadership team to really question the way they did things. So they did, they upped the ante. For the upcoming sessions no answer or hypothesis would remain unchallenged, either by the — now empowered — lab team or by other leaders in cross-feedback exercises. And it worked. They now had allies for a new way of working.

“You can’t force people to change, you have to make them want to.”

5. Create the space for creativity and get people to feel it.

It’s easy to forget that the higher up an organisation you go the more removed you become from the day-to-day that got you interested in the work to begin with. Being involved again for the first time in years had a profound effect on the senior leadership team. It helped show people that in small ways, they can start to spot their organisational debt, “the interest companies pay when their structure and policies stay fixed and/or accumulate as the world changes.” It’s those early shoots of new ways of working.

6. Collaborate between all departments (not just the sexy ones).

LABgobar had advocates in the senior team from across Senasa encouraging their own departments to take part. So while Tomas and his team started their work with senior leadership, it swiftly spread to working with just about everybody else. They held workshops across the organisation with ‘back office’ teams like finance, HR and legal, to the project teams running the day-to-day. Showing the methods, tools, hacks and craft of working in a new way shouldn’t be consigned to any one part of the organisation, you’ll need to work together.

With LabGobAr working across the organisation, they started to meet teams of frustrated public servants, hungry to do things differently, people keen to learn new ways of working. And that’s how they got interested in cows.

7. Have the humility to abandon your assumptions.

One interested team at Senasa had the idea of a $100 million fund to help pay out to farmers who’d lost their cows to Tuberculosis, a nasty disease that humans can catch too. But the Lab’s team wasn’t sure if a $100 million fund was the right answer, or if it was even the right question.

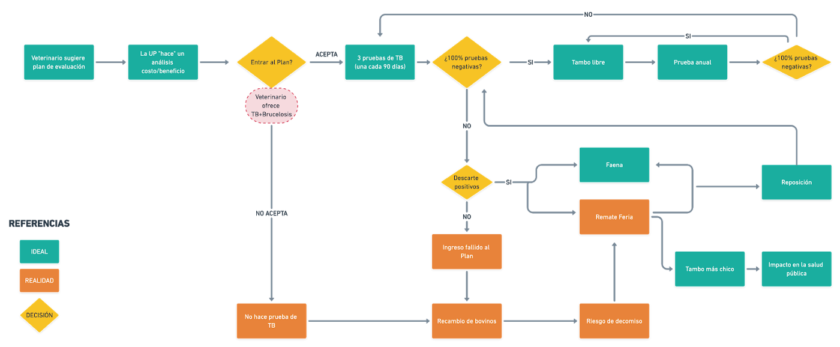

Together with the Senasa team they took the challenge back to first principles, and looked again at the whole process of maintaining a healthy meat and dairy industry. They compared the version as it was on paper — in theory — and another map of what actually happened. Side by side these two ‘journey maps’ had glaring differences.

8. Find a way to get out from behind your desk.

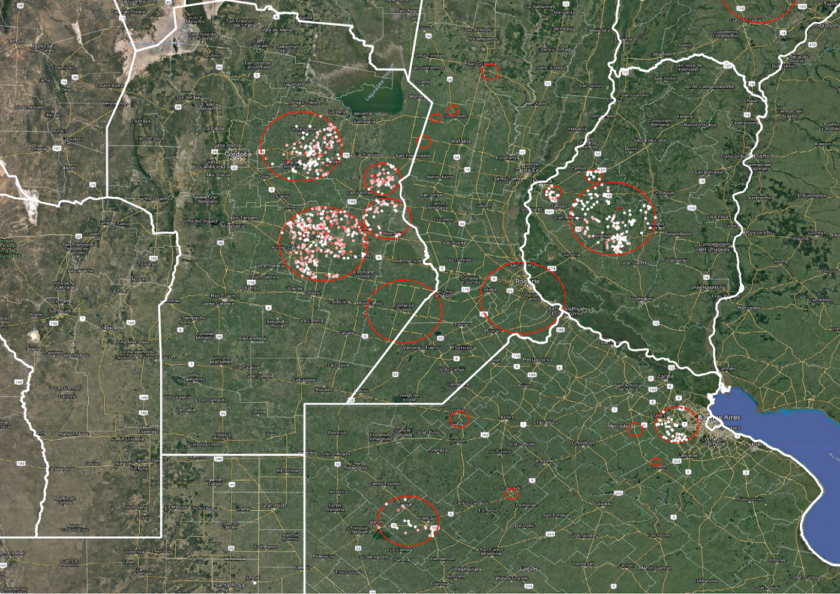

It wasn’t long before Tomas, his colleague Ol (the ‘behavioural’ guy) and their partners at Senasa were rattling around in backcountry Cordoba on their way to meet a local veterinarian. They’d used the data they had on Tuberculosis rates to find regions most prevalent with the disease and zoomed in on areas with high infection rates. These edge cases might shed some light on what the problem was.

“A desk is a dangerous place from which to view the world.”

As they criss-crossed between farmers, veterinary practices and producers they could finally put a face to the issues the industry were tackling. And what they found out hurt: apparently many veterinarians across the industry were issuing certificates of good health to herds of infected cows or to ones they’d never even inspected. The data on Tuberculosis was bad.

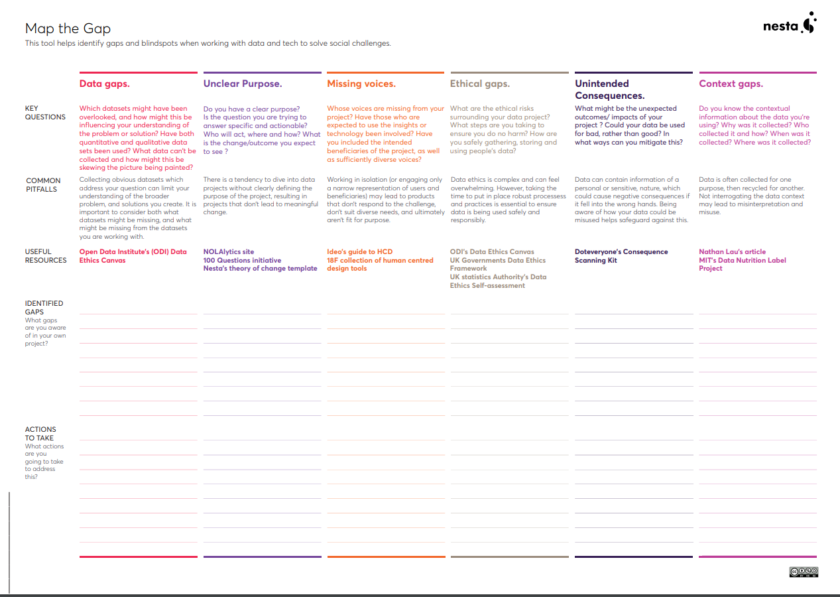

9. No data will give you a complete picture

All data has bias and blindspots. But in this case, faking the results of the tests had become a cottage industry. Sick cows were being covered up because the system incentivised it. The design of the perfect-on-paper process was fatally flawed, it was “built on 500 pages of untested assumptions” to quote Tom Loosemore. If the Senasa team had stayed in the office — rather than go out to the paddocks to interview — these unreliable numbers would have been guiding policy decisions and budgetary allocations for years to come. How good is the data you’re relying on? How do you know it’s good?

10. There are unintended consequences to everything.

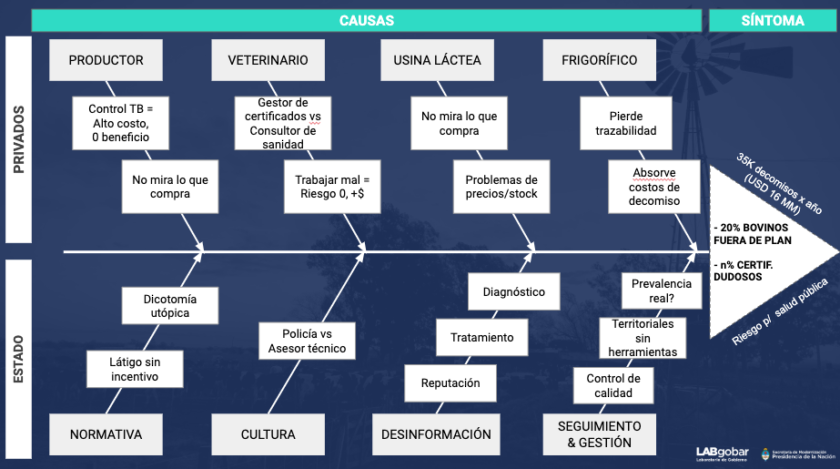

The team recognised the issue for what it was; a complex one. Back in the office they drew that up into a ‘fishbone diagram’, with personas of the different stakeholders involved which showed just how complex it can be. This wasn’t to obfuscate and overcomplicate, but to be clear on how interconnected these issues are. And what was at stake.

A bit of background. Argentina’s economy isn’t humming along. Economically speaking, cows are sacred in Argentina and the enormous beef and dairy industry props up the country. Buy a steak somewhere in the world and there’s an almost 10% chance it came from Argentina. There are more Argentinian cows than there are Argentinian people; 53.5 million of them.

When you connect the macro level issues — the reputation of a country or the potential for a public health tuberculosis crisis — and the micro day-to-day choices made in the fields, you make clear the interconnectedness of all issues. And you see your response as part of a whole. That matters whether the issue at hand is the unknown tuberculosis rates in your crown jewel industry, or a focus on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It might feel like it sometimes, but no-one is actually working in a silo, cocooned from the outside world (unless, of course, you work in a defacto Silo cleaning business).

11. It takes courage to stop a bad idea.

With all the evidence they’d collected it was clear the $100 million fund for farmers idea wasn’t going to work, not for this issue. But it helps if you can start to suggest alternatives (spotting the problem is usually the relatively easy part). The Senasa team now needed new ideas.

Under that pressure, the LABgobar team and their partners locked themselves in a room for a two-day design sprint, a pared back version of the famous 5-day sprint method. With an endless supply of coffee they developed ideas to test for the immediate, short, mid and longer term.

They A/B tested different messages to vets suspected of issuing fraudulent paperwork (the harsh message had more of an effect than the softly, softly approach). And they started drafting new legislation, one based on trialing and testing their assumptions as they went. They built a green paper in another one-day sprint, and after just a couple of weeks (!) they had validation of the reshaped legislation from different stakeholders (including non-government ones). Accelerating that process made it simpler and faster for the Senasa team to write a draft paper. It would only need revision and adjustments from the legal department before seeing the light of day. Senasa were thrilled: new regulation typically takes years, not weeks.

12. Don’t underestimate the power of building relationships.

Senasa’s default position had, over the years, become one of ‘police and enforce’. In the world of safe meat and produce, they were ‘bad cop’, with long lists of what people should not do. But with the project team going *literally* into the field, they (re) connected with those the organisation was there to serve. Actively listening to the issues faced by people day to day — in this case with their herds — helped a government institution better understand the needs of the people it hoped to support. That’s marked a shift at Senasa in rethinking their approach more generally, from an enforcement department, to one looking to support and guide those in need of help. Hilary Cottam persuasively champions the power of relationships in the welfare state, advocating that it should probably guide us all, in everything we do.

None of these challenges are unique to Argentina, or LABgobar. Governments around the world face complex issues that flow beyond the boundaries of their departmental logics. The issues they face might seem intractable, but whether it is now, soon, or at some point in the coming years, by sowing a seed of doubt in the way things are, you will open a door to the way things could be. And having the skills — and the outlook — to do that is probably step one on that journey. It might be in these small tangible pockets of change in our daily work and actions that we come to create the larger difference we hope to see in our governments and the world. Or Tomas puts it:

“changing tangible things without changing culture is very hard. But changing culture without changing tangible things, is impossible.”